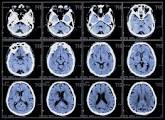

Tomorrow, I’ll go in for my eighth MRI. I’ve only had one MRI with positive results. Usually, there are more lesions. Usually, there will be new meds. These are tests I fail regularly. When I was in middle school, I got a 65% on the long division test. In high school, I failed a chemistry test. Later, I did not do well on the LSATs, but I didn’t really want to be a lawyer, anyway, did I? Life is too ambiguous to insist on being so sure.

Tomorrow, I’ll go in for my eighth MRI. I’ve only had one MRI with positive results. Usually, there are more lesions. Usually, there will be new meds. These are tests I fail regularly. When I was in middle school, I got a 65% on the long division test. In high school, I failed a chemistry test. Later, I did not do well on the LSATs, but I didn’t really want to be a lawyer, anyway, did I? Life is too ambiguous to insist on being so sure.

This past month, I filled out an application for a new doctor. “I don’t know if I can handle anymore rejection,” I said to my mother. I had received three manuscript rejections the day before. Still, I detailed my c-sections and my multiple sclerosis and my depression on the papers. I was accepted. It was a thrill! At my first appointment, I was polite. I tried not to seem overly needy. He explained to me about depression. I remembered my melancholy adolescence and drinking through college and nodded to him when he explained about the brain and chemicals. I thought about my grandmother. I wanted to explain to him what I knew about science and feelings. I’ve tried to control my brain chemistry with thought, and when I can’t–unsurprisingly!–have found the ultimate illusion of failure. Emotions and science have a complicated relationship.

Last month, when I opened the email from my servicer that my grace period was ending for my student loans, anxiety spiked. But I don’t have a full-time job yet, I said to the email. I have not yet received all the rejections from my manuscript! I needed more time to redeem myself, and I still continue to spend all the time in the world arguing this in my head. How easy it is to forget the many people in my shoes, also in the muck of the temporary plight of the humanities, people I don’t consider as having failed. To believe in failure assumes that the chances for success are finite. I feel like I’ve realized something as I type this, yet I know that in the face of a particularly hard rejection or a disappointment, I will forget again.

I have read all the articles about how to make an MFAW worth it, how to survive post-degree life, how to make the degree count for something, and though I do all these things because I love them, I wonder, as I always have, what defines a writer? How do you meet whatever measures and hurdles? How do you pass that test? To my students, I say, If you write, you are a writer, but do I believe that for myself? Sadly, not right now. Right now, I believe that if you can publish a book, if you can pay back the loans for your writing degree with a job you acquired as a result of that degree, then you are a writer. I don’t hold these beliefs about other people who write, but these feelings haunt me about myself. Feelings are not rational. And who knows how that will change with time? In ten minutes, while I’m jotting down notes about the novel I’m afraid to start, I might change my mind. Or I might be 80 years old with dozens of manuscripts and no books, and then, I might even consider myself a writer. There is something to be said for keeping on.

Around some people, I become unsure, and I feel like I am not who I am, or that I am flawed and my body is weak because it is diseased, or that I am doing the wrong things. Some people are just so sure. I ask my husband, “Why do I stay quiet? I don’t want to pass their tests. I want to politely disagree. I do not always want to be the world’s little sister.” And as I say this, my mind is back in the conversation with my mouth closed and my insides quivering with dissent. I don’t want to be told everything. I want to tell, too. At some point in my life, passing the test became about following directions, meant allowing myself to be told. How to fail, now?

A month or so ago, I took a Buzzfeed quiz that, in some psychic way, told me my biggest fear was failure by analyzing my favorite pictures from a selection. Yes, I chose a photo of a hand beckoning out of the dark. Yes, I chose the photo of a woman staring into an overgrown field. Sure, I chose the picture of a couple standing under an umbrella in the rain. Somehow, Buzzfeed was right, and they, whoever they are, passed the test: I am afraid of failure, and then I wondered if I had passed the Buzzfeed test by answering the questions right. Hey, who’s testing who here? I wanted to know. Buzzfeed has also told me I am sensitive, that my outgoing personality masks my introversion, and that if I were a hippie, my name would be Flower. They always pass, or I always pass. The thing about the pain of failure is that it’s a smack in the face to hope. I remember the initial failure I felt after each c-section, and how now, the failure of my body to do what nature intended has become gauze-like in comparison to my sons, who, in my mind, could not fail me if they tried.

While I’m in the MRI machine tomorrow, I will have an IV–my least favorite part. This is for “contrast,” something that makes me imagine neon hi-liter fluid coursing through my arms and legs and brain while I try to keep still. “Try not to swallow for the next minute and 40 seconds,” the radiologist will say over a speaker while the machine does its thing, sounding like ten squirrels dropping acorns on a hollow log. I will try not to breathe. I’ll hope not to gasp for air. Or heaven forbid, sneeze. No vivid thoughts, even. I might decide, at that moment, that I am not taking the test, that I am the object, the machine is the writer. This will not calm me. In a day or two, I will know if I passed.

This month, or this week, or tomorrow, I will be rejected from a literary magazine or a book contest. Usually, I will submit somewhere else. This month, I will reject someone’s manuscript with a softened heart. As a writer and editor, if I do what writers are supposed to do, and keep on, thinking to myself about Beckett’s “fail better,” I will be rejected far more times than I will actually reject. I will write something nice in the writer’s email, and what I really would like to do is take their address off the manuscript and mail them a personal letter on stationery with a blue Pilot Precise V5 ballpoint, telling them how close they were to being accepted and not to feel like they failed. After all, I’d made it to the end of their piece and had taken time to write that letter. In this way, I will tell.